Peter Watson, Nebraska's Veteran, Has a Narrow Escape.

LAST SHELL KILLS THE BEAST

Latest Encounter of the Professional Wolf Hunter Is the Most Exciting of His Career.

Special to The New York Times / September 3, 1899

CHADRON, Neb., Sept. 2. -- Probably the only remaining wild beast hunter in the State of Nebraska to-day, a survival of the pioneer days, is Peter A. Watson of this city, who has just distinguished himself in killing a great gray wolf in a hand-to-hand struggle, with a small revolver as his only weapon. Watson is a professional wolf hunter, and his prowess is recognized by the Nebraska Live Stock Association, which employees him annually on a salary to slay wolves on the range, and thus protect young stock.

For ten years Watson has been on the payroll of the State Stock Association in the capacity of wolf hunter, and he has killed on an average of 400 big gray wolves annually. Of late the catch has dropped down to less than 200 annually, but for the first few years of his occupation as wolf hunter for the association Watson killed as high as 500 wolves yearly.

In this pursuit Peter Watson has ridden his horse through the whole of Northwestern Nebraska, and has enjoyed many stirring adventures. He is the only man in the State to-day who makes his living by slaying wild beasts. This class of men has been gradually disappearing from Nebraska, driven further West by the advance of civilization. Trapping used to furnish occupation for a large number of these men on the streams in the Western part of the State, but all of that numerous class of daredevil spirits have been swept in late years into the fastness of the mountains by the farmer and the stockman. The probabilities are that Watson will not be able to earn his salary many more years, so rapidly are the wolves disappearing from Western Nebraska.

The man and his methods are equally curious. Watson is a tall, athletic frontiersman, past fifty-five, but as erect in his carriage as an Indian. His father, "Jo" Watson, was a famous Nebraska hunter, and shot buffalo with "Bill" Cody for the railroad company when the Union Pacific was poking its nose across the plains. He was killed in a wolf chase at Sidney several years ago. Peter Watson has rather a contempt for that class of hardy Westerners who made their living by trapping, and nothing makes him more angry than to have some one mistake him for a trapper.

Watson does all his hunting on horseback with a pack of fine staghounds. These dogs he breeds for his own use and always uses six of them in hunting. He rides a blooded horse that can keep well to the front in a chase even after the fleetest animal that roams the plains, the gray wolf. He works entirely under the direction of the Stock Association, traveling from county to county as the wolves are reported to be ravaging the range in different parts of the State. It is nothing for him to ride a hundred miles without dismounting, and he covers nearly twice that distance in a day when it is necessary.

He is always ready to take to the saddle, and his methods of conducting a wolf hunt are peculiarly his own. he rides into the section where wolves are reported to be killing young stock, and moves along until a wolf is sighted. He carries a powerful field glass, and is constantly sweeping the surrounding plains with it. In this way he frequently sees the wolves before they see him. If the game is off and away, Watson simply notes carefully the general direction taken; then he swings his pack around behind a hill, drops out of sight, only to reappear ahead of the game, in which he rides with a rush.

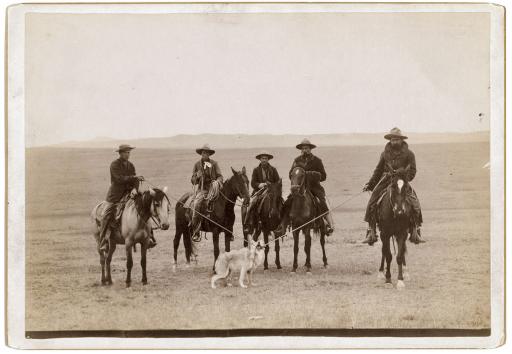

Cowboys take in a gray wolf on "Round Up" in Wyoming. 1887 photograph by John Grabill.

Then the dogs take up the chase. The wolf seldom holds out for more than a mile. Sometimes a particularly strong animal manages to run two miles before the hounds overtake him. The pack works together. if the dogs did not they would not last long, as the average gray wolf can kill in relays any pack of hounds that ever attacked him. But when Watson's trained pack jumps on a wolf, that is the last of him. They fight together and seldom get more than a scratch. The dogs follow the wolf closely and attack him all together, and such a fight lasts ordinarily but a few minutes.

Mr. Watson, in all his experience as a wolf hunter, has never found it necessary to aid his dogs in dispatching their prey after they have run it to earth. In fact, it would be hard to render service after the attack is made because of the indiscriminate mixture of dogs and wolf. On these wolf hunts the wolf slayer is armed with nothing but a large revolver. He has several times been forces to use his weapon in self-defense, for, while wolves not pressed, will never attack a man, occasionally a hard-pressed wolf will turn on his pursuers and make a most desperate fight.

This was the case a few days ago in Box butte County, where Watson was engaged in exterminating a number of big wolves which had killed some young stock. The pack had started a wolf and was far in advance of their master, when suddenly a huge wolf, which had evidently been asleep in the rank underbrush until disturbed by the wolf hunter's horse, sprang upon Watson. The animal buried his claws in the side of the horse and his fangs in the rider's leg. It was a very large wolf, and the suddenness of the attack gave the beast a distinct advantage.

The attack was made from the right side, and the only weapon the wolf hunter carried was beneath the body of the ferocious brute. Watson struck the animal repeatedly across the snout with his quirt. Then he thrust his hand down under the growling beast to secure his pistol. Instantly his arm was seized by the animal and the flesh torn from the wrist. Watson reached over and grabbed his gun with his left hand. The wolf still had the hunter's right hand between his teeth and was chewing it very industriously. Watson retained his presence of mind and fired two shots into the beast. He was forced to be very careful to avoid wounding his horse. Still the animal did not release his hold.

All the time Watson's horse was rearing and plunging over the prairies and screaming in agony. This made the rider's aim uncertain. Four times he fired at the wolf, and had but one shell left in his gun. Blood was streaming from the hunter's arm and leg, the horse was covered with blood, and the wolf was bleeding profusely. With an effort the wolf-slayer thrust his revolver into the mouth of the furious beast, and at the risk of blowing off his own hand, fired the remaining shell into the struggling target. The wolf's head was blown off and the body dropped on the prairie.

Weak from loss of blood, Watson climbed down, tied up his wounds, and throwing the animal across the horse started for home, fifteen miles away. The heavy leather covering he had over his limbs alone prevented his leg being torn from his body. Watson declares this to have been the most exciting experience of his long service as a wolf hunter. the animal was a female, and Watson is inclined to think she had some whelps in the immediate vicinity where the attack occurred or she would not have fought so hard.

Most of the animals killed by the wolves are not devoured, but their blood is sucked. In this manner it takes several young cattle to satisfy a very small number of wolves.

Watson carries the scars of a dozen encounters had with wolves during his service.