EARLY EXPLORATIONS AND THE PRESENT RICH MINES.

THE INDIAN RACES -- FERTILE FIELDS AND GRAZING LANDS -- A TRIP INTO THE BOWELS OF THE EARTH -- THE DAYS OF THE STAGE COACH

Newspaper Account / Dec 22, 1890

TUCSON, Arizona, Dec. 21. -- The word contrast fails to convey any conception of the differences to be found between Arizona and anything in the East. Though smaller than New-Mexico by 5,000,000 acres, Arizona is still large enough to contain the States of New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland combined, and one of its counties, Yavapai, is about as large as the State of Maine. These contrasts are not confined to mere matters of size; they are found in every department of natural science and civilization.

The dawn of civilization has just broken in this part of the country. There are many delightful people to be found scattered over this wide domain, but they are only an evidence of the smallness of the world after all. Talk with them and you instantly find that you have common friends in the distant East, or perhaps others have lived near your own home and know all about you. Side by side with these, however, are found the roughest elements of the New World — some struggling for homes, others for wealth, and others still living by their wits upon the weakness of their fellows. All Europe is represented here, and you will find the sturdy Northman working along patiently beside the stolid German or the more excitable Frenchman and Italian. There is no more curious comment upon the good work which America is doing for the world than this state of affairs. Races which are at swords' points are brought together and shown that they can work in the same yoke and pull together for a common end. The differences do not end here, however, for in the same region, sometimes unmoved by the spirit of enterprise which is making great changes all around them, and, again, partaking of the benefits thus brought to them in a greater or lesser degree, are the descendants of the older races of the continent. Many of the Mexican race have been warmed into activity by the rising sun of prosperity, and apparently are determined to profit by it. They are in many instances active leaders in this new life which has been brought to them, and no longer the indolent, sun-bath-loving children of the soil they once were. These are signs of the times, and will undoubtedly lead to greater things, for this race is the most hopeful of all the natives.

It is doubtful whether the Indian ever can or will be able to change his nature sufficiently to allow him to become a good, peace-loving citizen and take up the quiet arts of a fixed home life. The spirit of restlessness seems to have been born into him, and our system of reservation camp confinement serves only to bottle this spirit up until it can no longer stand the strain, when away he goes. Of course there are exceptions to this, as, for example, the Indians on the San Carlos reservation, many of whom have become good farmers and realize handsome profits from their lands. But even among these Indians there are wild individuals, who, furnished with a permit from the authorities, go off hunting and do great damage. It is true they often have provocation, but quite as frequently there is none at all, as they have been known to kill men for the sake of their ammunition. The mischief of it is that these fellows are usually armed with the best rifles and ammunition obtainable and with their inborn huntsmanship they are able to waylay the most careful white man and are generally sure to outnumber the party they attack. It should be made a punishable offense for any Indian who has ever run away from a reservation, or who is not peacefully settled upon one and has a good record, to own a rifle or to be found with one in his possession. There are some Indians who can never forget their grudge against the white man, and will always hunt him down when they have a chance, apparently shooting him for the pleasure of it. The only way to protect the men who are building up our Western country is to keep such characters in pretty close confinement.

It is doubtful whether the Indian ever can or will be able to change his nature sufficiently to allow him to become a good, peace-loving citizen and take up the quiet arts of a fixed home life. The spirit of restlessness seems to have been born into him, and our system of reservation camp confinement serves only to bottle this spirit up until it can no longer stand the strain, when away he goes. Of course there are exceptions to this, as, for example, the Indians on the San Carlos reservation, many of whom have become good farmers and realize handsome profits from their lands. But even among these Indians there are wild individuals, who, furnished with a permit from the authorities, go off hunting and do great damage. It is true they often have provocation, but quite as frequently there is none at all, as they have been known to kill men for the sake of their ammunition. The mischief of it is that these fellows are usually armed with the best rifles and ammunition obtainable and with their inborn huntsmanship they are able to waylay the most careful white man and are generally sure to outnumber the party they attack. It should be made a punishable offense for any Indian who has ever run away from a reservation, or who is not peacefully settled upon one and has a good record, to own a rifle or to be found with one in his possession. There are some Indians who can never forget their grudge against the white man, and will always hunt him down when they have a chance, apparently shooting him for the pleasure of it. The only way to protect the men who are building up our Western country is to keep such characters in pretty close confinement.

The representatives of the other native race to be found here are a puzzle. They seem, in spite of their past history, of which they have left indelible traces on every hand, to be utterly dead and hopeless to every opening of the new future. These are the descendants of the Aztecs, or Toltecs. To them the coming of the white man, instead of being a sign of renewed prosperity and peace, as Montezuma predicted, has only meant disease, idleness and beggary, and if it were not for the feeling of disgust which their appearance creates their condition would be almost amusing. They and the other Indians who inhabit the northern portions of Arizona have lost all the poetic characteristics which have been woven about them by the great writers of fiction and have become a lot of good-for-nothings.

The other contrasts referred to are in the field and nature. The physical features of the country are most extraordinarily diversified. There are the most fertile fields, fine grazing lands and meadows in the river bottoms lying side by side with a true desert or extensive lava flows. The land varies in height from a portion which lies about on the level of the sea in the southwest to plateaus which range in height from 7,000 to 8,000 feet, and these break up into mountains, which reach the grand elevation of 14,000 feet in the San Francisco range. Nowhere in the world is there such a gigantic evidence of the power of erosion as is found spread out in the Colorado cañon. [the Grand Canyon – Ed.] Its praises have filled the papers and scientific journals for several years, and descriptions of this wonder, brought to light in the nineteenth century, have been read by almost everybody, but it is none too well known even now. The railroads have brought it within easy reach of all who are fond of nature and of exploring her choice treasures. That it was due to erosion there can hardly be any further doubt since the careful study of its geological problems. The little bits of it which the ordinary traveler sees and raves about are, indeed, wonderful enough, and, perhaps, serve to convey some slight idea of its grand proportions, but that is all. No description, however powerful, can equal the impressions produced by a single glance. This region will richly reward the geological and archaeological investigator.

Historically, this region is of great interest to the student of early American explorations. It is due to some of the survivors of the ill-fated expedition of Navaraez on the coast of Florida in 1527 that we have our first account of some of its wonders. The unlucky men who formed the land party of this expedition, after wandering about for some time in search of golden treasure and the fountain of perpetual youth, and finding nothing but venomous and repulsive reptiles, returned to the coast, where they searched in vain for their ships, which had given them up as lost and had returned to Cuba. From their stirrups and other available bits of iron they made instruments by the aid of which they constructed five boats, in which they set out for Cuba. All were lost but those in the boat commanded by Cabeza de Vaca.

According to his story they remained with the Indians into whose hands they had fallen as slaves for about six years, when they effected their escape. Only four of them reached the mainland, and here they were in a rather desperate condition. They chose between the dangers of the sea and an overland journey to make the attempt to cross the continent and rejoin their countrymen in Northern Mexico. It was a bold resolve, but the men of those times had the courage and endurance for such undertakings. They crossed the greater part of Florida, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, and reached the banks of the “great water†ten years before De Soto stood upon its shores and found a resting place beneath its troubled waters. They crossed the plains, came to the valley of the Arkansas, and followed it up. Entering New-Mexico, they came to the Indian pueblos on the Rio Grande. Then, going further westward, they came upon the Zuni and Moqui villages, and their description of these places represents them very much as they are to-day. Everywhere they were received with the greatest hospitality, the Indians regarding them with considerable wonder and treating them as superior beings. They succeeded in making the cause of their coming and the object of their journey understood, and the Indians pointed to the south. After many hardships and trials they at last saw once more the banner of Castile and Leon floating from the ramparts of Culiacan, in Sinaloa. Their arrival was as much of a surprise to their Spanish brethren as it had been to the Indians along the route.

The story of their journey reads like a romance. Of course the glowing accounts of Cabeza de Vaca gave rise to further expeditions to these regions. These had two objects. The first which set out was led by Padre de Niza, and was designed to convert these pagans to the true religion. They reached the region of the San Francisco Mountains and came within sight of the mysterious “seven cities,†but the messenger sent forward to the first city incurred the wrath of the Indians by an imprudent act, and had his brains dashed out as a consequence. The father, hearing of this, decided that their minds were not in a fit temper to receive the Gospel truths, set up is banner, called the country the new kingdom of San Francisco, and returned.

In 1540 Coronado set out from the Culiacan with a thousand men, in search of gold and glory. He passed through the greater portions of Arizona and New-Mexico and reached the site of the Denver of to-day, when he returned to Mexico after two years of wandering, in which his hopes had been disappointed.

The northern portions of both New-Mexico and Arizona were obtained for the United States by the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1847. And that part south of the Gila River, in these two Territories, formed the “Gadsden purchase†of 1854. The whole region went by the name of Arizuma among the Spaniards as far back as 1580, the name being derived from two Pima words which mean “little creek.†Other authorities derive from the words “ari,†a maiden, and “zon,†a valley or country, undoubtedly referring to the traditional maiden who once ruled over the Pima Nation. This great tract of land was separated into two territories in 1868. Thus, after 350 years, this region, one of the first discovered in the New World, is now becoming better known. The iron horse, that pioneer of progress, came in 1880, and has brought the news to the Nation of the richness of her mines, the fertility of her soil, and the healthfulness of her climate.

The northern portions of both New-Mexico and Arizona were obtained for the United States by the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1847. And that part south of the Gila River, in these two Territories, formed the “Gadsden purchase†of 1854. The whole region went by the name of Arizuma among the Spaniards as far back as 1580, the name being derived from two Pima words which mean “little creek.†Other authorities derive from the words “ari,†a maiden, and “zon,†a valley or country, undoubtedly referring to the traditional maiden who once ruled over the Pima Nation. This great tract of land was separated into two territories in 1868. Thus, after 350 years, this region, one of the first discovered in the New World, is now becoming better known. The iron horse, that pioneer of progress, came in 1880, and has brought the news to the Nation of the richness of her mines, the fertility of her soil, and the healthfulness of her climate.

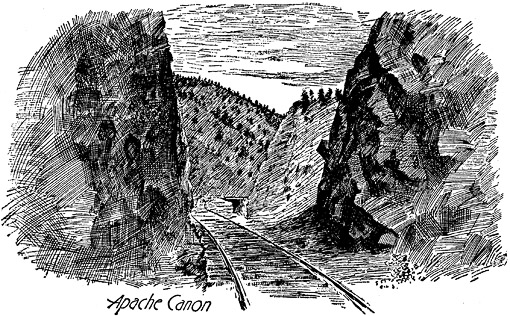

In the early days much of this travel was done by stage, but the railroad is rapidly driving out the buckboard and the Concord coach. In the words of one of the venerable Jehus of those times, "Stage drivin' will soon be played out in Arizona, and these infernal kyars will be runnin' to every town and mining camp in the whole blessed country." Many were the pleasant hours passed on these old rattletraps, and many were the thrilling tales of the lonely ambush, the sudden attack, the groans of the dying, and the wild race for life over mountain, hill, and plain. The great route in the olden time and the only means of communication was the Butterfield line, from Marshall, Texas, to San Diego, Cal. Now, two transcontinental railroads cross the Territory, one in the north and the other in the south. The regions through which they pass are not very inviting, and the stranger gazing at the vast stretches of dried, treeless plains and barren mountains is not apt to be favorably impressed with the country. But nearly every one of these mountain masses is rich in minerals, and north and south of these lines the country presents a very different appearance. Many prosperous towns have sprung up, cattle ranges have been established, and almost everywhere that capital has sought an investment it has been successful.

It is entirely wrong to believe that Arizona is incapable raising the traditional “hill of beans,†for in many places there are men who, judged by the standard of the old proverb, that “He who caused two blades of grass to grow where one grew before, was greater than he who took a city,†would be among our noblest citizens. We are very apt to judge from appearances only, and are quite as apt to be mistaken. It is well to recall the remark of Daniel Webster concerning the "Golden State," that "a bushel of wheat would never be grown within its limits." To-day the traveler will see the valleys once considered as valueless as the Desert of Sahara, and apparently quite as incapable of cultivation, as fine farms as are to be found anywhere in the West; he will find comfortable homes, surrounded by gardens and orchards, and he will become convinced that this desert has been made to blossom and produce bountifully everything that grows under a tropical or a temperate sun.

The truth is that its capacity is only beginning to be understood. Everything which has been said of the fertility of the soil of Colorado and New-Mexico is applicable to Arizona. Wherever water can be obtained for irrigation the dry, arid valleys undergo a transformation as sudden as it is beautiful. At present these farming lands are confined largely to the valleys of the principal rivers, the Gila, Salt, Verde, Santa Cruz and San Pedro, but there are millions of acres of fine soil among the hills and mesas which are as yet unoccupied. There is ample evidence that these places were densely populated in the remote past. The ancient inhabitants of this region understood the value of irrigation, as the traces of their canals are to be found far beyond the present limits of cultivation.

Maricopa, or, as it has been called, the “garden of Arizona,†is the leading agricultural county of the Territory. It lies along the lower valleys of the Gila and Salt Rivers, and it has been estimated that there are 400,000 acres of arable land in this county alone. For fruits and grain it stands unequaled. One has only to travel along the banks of the Gila in the neighborhood of Phoenix to be convinced of the possibilities of that region. It is hard to realize that the first American settlement was made in this place in 1868, and that all this transformation has taken place in the short interval of about 20 years. Then the sun beat down upon an arid plain covered with greasewood, mesquite, and cactus, and its rays served only to scorch the struggling vegetation. A narrow strip of verdure marked the presence of the river and relieved the eye from the glare of the desert. It would be hard to find a more perfect picture of nature in her wildest and most savage mood. Now great fields of wheat and barley stretch away for miles, acres upon acres of alfalfa gladden the eye, and orchards are to be found on every hand. In this single valley only one-fifth of the available lands have been reclaimed. All that was said of New-Mexico in regard to fruit raising and grape culture applies equally well to Arizona. In addition, the sugar cane and the cotton plant thrive in these rich valleys, and it would be unfair to omit any reference to the native plants, many of which would prove a profitable source of revenue if cultivated. I refer to those which have long been utilized by the original inhabitants for their valuable properties for domestic purposes or in manufactured articles. Among these are the maguey, or mescal. In Mexico, it is largely cultivated and becomes an important item of revenue to the State. From it, a distilled liquor is made containing a large percentage of alcohol. It is as clear as gin, and has the strong, smoky taste of Scotch whisky, and will intoxicate as quickly as either.

From the fiber of the plant of course, fall is made, and the paper of an excellent quality is produced. Then there is the AA, or soap lead. This plant grows in profusion on all the dry plains and rolling appliance of the country. From its long, narrow leads excellent rope, paper, cloth, and other fabrics are made. Its roots are used by the Mexicans as a substitute for soap; a heavy latter is made by agitating the crushed roots in water, and it is said to have superior qualities over ordinary soap for watching the flannels. It is also used as a wash for the hair. There are many others which might be mentioned, such as the ochetea and cholla, a species of cactus, much used for fencing; the hedeundilla, or greasewood, an evergreen which seems to be indigenous to the country, from which a gum that exudes resembling in color and quality gum Arabic.

From the fiber of the plant of course, fall is made, and the paper of an excellent quality is produced. Then there is the AA, or soap lead. This plant grows in profusion on all the dry plains and rolling appliance of the country. From its long, narrow leads excellent rope, paper, cloth, and other fabrics are made. Its roots are used by the Mexicans as a substitute for soap; a heavy latter is made by agitating the crushed roots in water, and it is said to have superior qualities over ordinary soap for watching the flannels. It is also used as a wash for the hair. There are many others which might be mentioned, such as the ochetea and cholla, a species of cactus, much used for fencing; the hedeundilla, or greasewood, an evergreen which seems to be indigenous to the country, from which a gum that exudes resembling in color and quality gum Arabic.

With regard to the fauna, there is not much to be said. The same species which are to be found further north are met with fear; all the “big game" is well represented, and there are some forms of "varmint" peculiar to the place. We are all well informed that "snaikes and tarantulers and Healy monsters is powerful bad in Arizona," and that "Injuns" are to be found behind every rock, but this is a delusion. The only peculiar beast which deserves mention is the Gila monster referred to above. It belongs to the lizard species, is a blackish-red color, covered with scales, and has everything but a prepossessing appearance. It sometimes reaches the length of two feet, and makes its home on the dry and barren mesas of the southwestern part of the Territory. As far as I can ascertain, it is entirely harmless. To the new arrival, however, who discovers it upon a rock with its mouth sending forth a greenish, frothy slime and puffing like a small steam engine, it presents a very formidable aspect.

Up to the present time the greatest interest in Arizona has centered in its mines. There is gold which Cabeza de Vaca led Coronado and his followers to expect was to be found by the use of the sword and not the pick, and consequently they were disappointed; but the amount of hidden treasure which they passed over on their journey was far greater than that which Pizarro wrung from his Peruvian captives or that which Cortez found in the halls of the Montezumas. They were not men who were willing to dig for gold. The first efforts in this line were made by the Jesuit fathers, as is witnessed by the old shafts and tunnels in the mountains surrounding the missions. These works were on an extensive scale, judging from the ruins and the large piles of slag, which are still to be seen. The success which attended their labors produced a great excitement in both Old and New Spain. Their methods were crude, and only the richest mineral or ore entirely free from the baser metals could be worked at all. The Mexican war for independence put a stop to all mining operations in both Sonora and Arizona. From that time on the mining industry of the region had a precarious existence, and nothing but its intrinsic value ever kept it afloat. At the time of the Gadsden purchase there was scarcely an operating mine in existence. Our civil war gave it another blow. At that time not only did the Indians kill, burn, and destroy everything they could find, but outlaws from the Mexican border, believing that our government was going to pieces, aided the murderous Apaches in their work of destruction. It was only when the Indians were placed upon reservations, in 1874, that the inhabitants began to have a breathing spell.

The new era of mining operations began in 1877 and 1878 by the discovery of rich fields in both Northern and Southern Arizona. In this line, Cochise, and the southeastern corner of the Territory, is the banner county, and has well earned that distinction in the richness of its ore bodies and their extent. The famous mines of Tombstone were located by A. E. Shieffelin in February, 1878. He had been warned, as he left Camp Huachuca, that he would find a tombstone instead of a fortune in Cochise’s domains, but he pushed on and discovered the mines which have attracted world-wide attention since then, he named them from this incident.

The mining town of Bisbee, is where the Copper Queen Mining Company has its headquarters. The town itself is a characteristic mining camp, with all the modern improvements and with a great many advantages not usually found in such places. The New-York men who are interested in the place have left very little undone in the effort to make their employes comfortable. They have provided an excellent library and reading room and a well-furnished hospital, with competent medical attendants, for the use of the men, and both of these institutions are highly appreciated. The mines honeycomb the mountain sides to the distance of thirty-five miles and have reached a depth of 400 feet. The ore occurs in oolitic limestone, and at the 800-foot level the ore body is about eighty feet in width. The ore is composed largely of carbonates and oxides, and contains sufficient fluxes for smelting.

The Copper Queen company is the leading mine of the camp, and the description of its works will suffice for all, as it is one of the greatest mines of Arizona. We were first lowered down a long inclined plane to a depth of 400 feet an angle of about forty-five degrees, and were then about 280 feet below the surface of the ground. Here our wanderings began, and for nearly an hour we walked around guided by one of the foremen, who discoursed to us ably upon the characters of the different kinds of rock that we passed through. In one place it was limestone, in another ledge matter of varying quality, sometimes rich in copper, and then again left behind, because not quite as promising, but reserved for future working, as a sort of bank account to draw upon later. Here and there we passed rich masses of malachite and the beautiful azurite crystals scattered among the common ores, these forms being the most attractive.

I, however, was not yet satisfied with what I had seen and left the party under another foreman, whom we had just met down in the subterranean gloom, and then the fun began. Heretofore, we had been tenderly cared for and our paths had been pleasant and our shoe polish respected, but now all was changed. We climbed up ladders and down ladders, scrambled up through narrow openings, and jumped down through dark holes, and occasionally had the performance made very interesting for us by receiving a ducking as though the gnomes resented this invasion of their abode and meant to make sure that it should not be repeated. Finally, after many trials, my six-foot giant announced that we were 100 feet below the point at which we had left the party. I was glad of the information, because I should not have been surprised if he had said we were approaching China, so completely was I wound up. I thought I knew something about pathways and "trails," but have to admit that it would have been almost a physical impossibility for me to have retrace my steps.

The next trip was made down an elevator, which would astonish the every-day traveler considerably. My guide told me to get on the iron frame and then went to the engine, turned it on, and jumped on the elevator himself. On our way down, I asked him how he proposed to stop the thing, and his reply was far from reassuring --- “He reckoned the thing would stop of itself when it got to the bottom." I was preparing for a jump, when, sure enough, it did stop, not as I had anticipated, but quite gently, and, to my utter astonishment, swash into a puddle of water over our shoe tops, and both of us jumped and got into the driest place we could find. This condition of things elicited in the remark "that the water had riz some lately." Evidently something had happened, because from this point on, a Boyton suit would have been serviceable. Plunging on through the drifts, we came to a most interesting spot, where we stopped for a few minutes to watch the diamond drill grind its way into the rock, feeling out, as it were, for new beds of ore. We were at the lowest level reached by the mining operations, some 420 feet below the surface, and after looking around a little longer, examining the large pumps, &c., we started for the shaft, and at a rate which almost took our breath away good-natured "Tom" and I were hoisted to daylight in true miners' fashion on the top of an ore car, having had a good time together and having enjoyed our game of "follow my leader" underground very much.

Upon reaching the surface the ore is mixed in the proper proportions with coke, and the fluxes necessary for its reduction are shoveled into the roaring smelters, day and night, in one continuous stream. There are three single smelters and one double one, which are constantly at work, and they turn out about 280 tons of copper per diem. Last year the Copper Queen produced 5,049 tons, and the Holbrook and Cave 1,280 tons of copper. The three leading copper producers among our States, according to the latest statistics, in their order, are Montana, with 98,000,000 pounds; Michigan, with 86,000,000 pounds, and Arizona, with 32,000,000 pounds. These States may be said to produce our copper, because the next on the list is Utah, with only 2,000,000 pounds, our total production being 226,000,000 pounds.