(1903 reminiscence by a “former trooper,” perhaps faulty in certain details, of the recovery some 30 years earlier of four sisters taken captive by the Indians who killed their parents and brothers)

Ottumwa Courier / August 13, 1903

AN INDIAN CAMPAIGN

GENERAL MILES’ PURSUIT OF CHEYENNES IN TEXAS.

Former Trooper Tells of Frontier Experience in 1874-75 -- An Indian Massacre and Miles’ Expedition to Pursue the Guilty Indians.

The recent retirement of General Nelson A. Miles calls to mind the expedition against the Cheyenne Indians in the fall and winter of 1874-5 and the spring of 1875 in the Indian Territory and northern Texas. A participant in the expedition who at present lives in Omaha, tells the following story.

“The causes leading up to that expedition were the outbreaks of the southern Cheyennes along the Kansas border. A number of persons were killed and large numbers of livestock were run off into the territory by the Indians. The buffalo were gradually but surely disappearing. The troops then in that section of Kansas were the Fifth United States infantry and the Sixth United States cavalry and the Fourth United States artillery. A greater portion of the scouting through Kansas devolved upon the Sixth cavalry, while the Tenth United States cavalry operated from the vicinity of Fort Sill and the Fifth United States infantry then commanded by Colonel Miles operated from Fort Dodge, Kansas. The Sixth cavalry headquarters were in the winter at Fort Riley and in the summer at Fort Haynes, from which point the regiment made regular and frequent reconnaissance through southern and western Kansas to keep watch an [sic] the Cheyenne and Arapahoe Indians, who were constantly raiding the frontiers, and were extremely reluctant to remain on the Indian Territory reservations assigned to them.

Discovery of a Hunting Party.

“In the intervals of scouting duties the troopers were often sent out on hunting expeditions after buffalo, to supply the post larders with that excellent, and then plentiful, meat. It was on one of these hunting expeditions that a party of the Sixth cavalry discovered on the Smoky Hill river bottoms, some twenty or more miles southeast of Wallace the mutilated remains of the Jerman family, who it was afterwards learned had passed through Wallace enroute to Texas about a week previous. The wagons, two in number, had been burned, and one of the men in addition to nameless mutilations, was partly burned with the wagons. The elder Jerman was lying some distance from the wagons, his body fearfully bloated and mutilated. Both men were stark naked and were also scalped. Nearer the river lay Mrs. Jerman, in a partly nude state with an arrow sticking in her breast. She too, was scalped and otherwise mutilated. Two of the oxen and two mules had also been killed with arrows. All of the bodies were in an advanced state of decomposition and all of them were partly torn and devoured by wolves and buzzards that had been feasting on them but were scared away by our presence. The remains were found about September 5, 1874, and had evidently been killed two or three days previous. We buried the three bodies in one grave in the sand, and, marking the spot, returned to Fort Wallace to report the ghastly find.

“The arrows found in the bodies indicated that the murderers were of the Cheyenne tribe, and the trail they left behind them showed that they had crossed the Smoky Hill, going southeast.

“At Wallace we learned that the Jerman party had originally consisted of Mr. and Mrs. Jerman, a son and four daughters. Of the latter two were young women, aged 18 and 20 respectively, and two little girls, aged 7 and 5 years. The girls had all evidently been taken as captives with the Cheyennes.

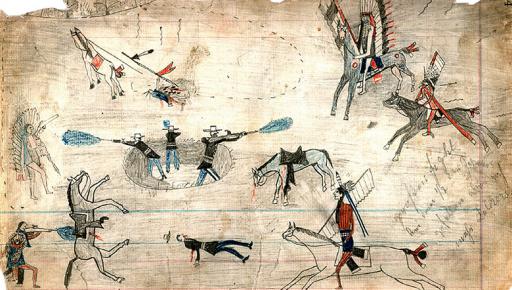

Kiowa ledger sketch of an 1874 skirmish in the Red River War, the conflict in whose context the German Massacre occurred.

Pursuit Promptly Made.

“After reporting at Fort Wallace, we were at once ordered to proceed back to Fort Hayes, where an expedition was at once started out in pursuit of the Indians, with the intention of recovering the girls before they crossed over into the Indian Territory, for which point they were evidently making. The intelligence of the massacre and capture spread very rapidly, and orders were sent out from the headquarters of the department of the Missouri, to hasten the formation of an expedition from all available troops in that section, to rendezvous at Fort Dodge, on the Arkansas. General Nelson A. Miles was placed in command of the expedition, and it was not until November 1 that the expedition set out from Fort Dodge. The troops comprising the same were the Sixth cavalry and Fifth infantry. The Tenth cavalry was ordered from Fort Sill to join the expedition en route, and the Eighth cavalry, from Fort Stanton, N. M., was ordered to prevent the Indians from entering that territory if too closely pressed by the pursuing troops.

“The Sixth cavalry and Fifth infantry comprised the pursuing force, and the command did not reach the base of operations at Camp Supply, Indian Territory, until November 8. But little time was spent in completing arrangements for the immediate and persistent pursuit of the Indians, and after one day’s camp at Camp Supply the expedition started out in light marching order for the head waters of the Red river, where it was ascertained by scouts that the Indians had taken refuge, and were under the chieftainship of Red Calf, the wiliest and most desperate of the Cheyenne tribe. A cantonment was made at the Salt Fork of Red river, and from there active operations began. The country was excessively wild, and almost wholly impassable for wagons, so that most of the necessary supplies had to be taken on pack mules. The infantry was left to take charge of the cantonment, and scouting parties of two companies of cavalry each were sent out to scour the country for signs and evidences of trails.

Indians Hard to Catch.

“The Indians, in accordance with their usual tactics when pursued, finding themselves closely pressed, separated into small bands and took refuge in the brakes of the Staked Plains. It was next to impossible to know with which party the girls were, but sufficient had been ascertained by the scouts that the four girls were still alive, and were with the main band. Finally, about November 20, a battalion of the Sixth cavalry encountered a body of Indians some twenty miles from the cantonment, in a broken region of country bordering on the Staked Plains, and after a brisk brush with them, in which four Indians were killed,

succeeded in scattering the Indians badly. A detachment of the command was acting as a rear guard. After the scrimmage was mainly over the main portion of the command crossed over a timbered bottom and had ascended the high ground beyond. As the rear guard approached the bottom, a couple of Indians were observed sneaking out from the canon on the other side, and they began a desultory fire with arrows at a copse of undergrowth below us, but on the other side. A squadron of the rear guard hurried across the bottom and took after the two Indians, while a couple of troopers rode down to the copse of undergrowth that they seemed so anxious to perforate with arrows.

Find One Child.

“The object of the Indians opening up a fire on this particular spot was soon made manifest. For the two troopers discovered to their surprise that a sleeping and sadly emaciated child lay there, wholly oblivious to the battle that raged about it a short while previous. The child was a little girl about 5 years old. Her little eyes were red and swollen with long weeping and she was sobbing in her sleep when they found her. Her clothes were in rags. There were no shoes on her little swollen and torn feet, and her flaxen hair was matted and unkempt with dirt and blood. The troopers awoke her gently. She seemed much bewildered at first and then began to cry, pleading that she might go home to mamma, and that she would be so good if they would only take her home to mamma. She was finally quieted and seemed to realize that she was in the hands of friends, and then in a childish lisping manner, plead that they would get her sister too. When asked where her sister was she pointed to another copse a short distance away. The two men carried the child to the point indicated, and they are found another sleeping sobbing child, apparently two years older than the one they first discovered. When she was awakened she looked at the soldiers with the utmost amazement, and demurely asked: ‘Well, what Indians are you?’ She was speedily assured that her rescuers were not Indians, but friends. Then the two little sisters were almost hysterical in their joy to know that they were no longer in the hands of the Indians. Said the elder: ‘Now we will get cake and candy, won’t we?’ The troopers were not certain about the candy, but they assured them that if there was any kind of cake in the commissary department that they should have it.

Had Been Brutally Treated.

“The two troopers signalled their discovery, and were shortly afterwards joined by several of their comrades, and word was at once dispatched to the advance of the important find of the two children. The command was halted and the two children were taken in charge by the surgeon accompanying the battalion. They were the two saddest looking little mortals that human eyes ever rested upon. They were nearly famished for food, and both bore pitiful evidence of the most brutal and horrible treatment since their captivity. They were given the best of care, and provided with an abundance of the best of food that the expedition could supply. They were almost frantic in their appeals for sugar, and were finally supplied it in moderate quantities. They were too young to tell much of their incredible sufferings and brutal treatment. It was, however, learned that their two older sisters were with another band of Indians, that had separated from the party which had them in charge, two or three days before. It was then deemed expedient to return to the cantonment and start out with new equipments and on another trail, which, from the story of the rescued children must have been south and eastward from the Red River cantonment. As this band the command was now in pursuit of had been amply punished and badly scattered, and as the main object of the expedition was the recovery of the Jerman captives a return to the cantonment in all haste was ordered.

“It was learned from the little girls that they were unaware that their mother had been killed. They had been told by an Indian who could talk broken English that their mother was with another party and that they should soon join her. They did not know what became of their father or brother. Since their captivity they had been subjected to every brutality that the devilish cruelty of an Indian could devise. Sometimes they were compelled to walk for miles and when they gave out they would be kicked and beaten until they were unconscious. Sometimes they would be compelled to ride astride on a very bony pony, and they often fell off, and were then tied on the animal, lying flat on their backs on top of packs. Their two elder sisters were beaten and abused terribly, and cried nearly all the time. They were not permitted to talk to each other and when they would forget and talk to each other and [sic] Indian would come up and knock them down and kick them. The children were finally sufficiently recovered to permit of their being sent to Camp Supply, where they can be more carefully looked after.

Search for the Older Girls.

“Immediately after the return of the expedition to the cantonment it was refitted and started out after Stone Calf and his band, with whom it was quite evident the elder Jerman girls were still held in captivity. This expedition and several others following it were fruitless of results. The winter had now set in early and the country was largely under snow, which obliterated all trails. In the meanwhile the Tenth cavalry had been caught in a terrible blizzard or ‘norther’ at its cantonment on the Sweetwater and suffered terribly. Several of the command were frozen to death, and they had become exhausted of rations. Horses and mules to the number of over half the command had perished from the cold, and thus crippled the Tenth cavalry started on its return to Fort Sill through another severe storm. The storm kept increasing in severity and twenty men and an indefinite number of horses and mules perished on the road back. The wrecks of wagons and the bones of the perished animals still mark the route of that fearful November march.

“Coincident with the movement of the Tenth cavalry, the Fourth cavalry, under command of Colonel McKenzie, operated against the Indians from the Texas station. This regiment captured one entire tribe of marauding Indians, that simultaneously with the outbreak of the Cheyennes, undertook to raid through northern Texas. These Indians were surprised in their camp near the southern border of the Staked Plains, and, deprived of their ponies, 4,000 in number, and were sent back to their reservations in the territory. The ponies were nearly all killed by the orders of the government, such a procedure being deemed the best way of putting the marauding Indians hors du combat.

Final Rescue of the Captives.

“The Eighth cavalry had accomplished effective service in heading the Indians off on the Cimarron and Canadian river trails into New Mexico, so the only recourse now left for the Cheyennes was to return to their agency on the Cimarron or suffer severe punishment and the deprivation of their ponies. At intervals during the winter scouting parties were sent out from the cantonment on Red river, and it was not until February that the Indians, after incredible hardships during the excessively severe winter, concluded to make their way to the agency. They managed to elude observation until they reached the almost impassable labyrinths of a Washita river midway between the Red river cantonment and Fort Sill. Their trail was found there, and immediate pursuit was taken up and the band was overhauled before they reached the Canadian river. Here Stone Calf, who was himself suffering from frozen feet, surrendered his tribe to the Sixth cavalry, with the two elder Jerman girls. The Indians were promptly disarmed and escorted to the agency, on the Cimarron, and were turned over to the Indian agent there.

“The condition of the captive women was pitiful. They had been subjected to every conceivable outrage. Their limbs were badly frozen, and both were placed in the hospital for treatment, where they were given every kind of attention that the military and Indian agency authorities could bestow. From the moment of their capture to the day of their rescue they had been repeatedly whipped and their bodies were a mass of sores and bruises inflicted by their captors. They were condemned to absolute slavery and were beaten and cudgeled worse than if they were brutes. They were both the witnesses of the horrible murder of their parents and were denied the privileges of caring for their younger sisters, and were also denied the comfort of talking with each other while in captivity. As soon as they were sufficiently recovered to travel they were taken to Fort Leavenworth, and were partially restored to health and to their friends. During their captivity they were compelled to walk all the while, and from the effects of their terrible exposure they both became permanent cripples. The two younger children were also sent to Leavenworth, where they were rejoined by their elder sisters, and all eventually returned to Arkansas, their former home.”