Newark Daily Advocate / September 4, 1897

Frank Phiscator Found a Big Fortune in the Klondike.

HORRORS OF ALASKAN WEATHER.

Young Prospector Makes Five Millions of Dollars in Fifteen Months -- Perils of the Trip -- Death Strews the Way With Skeletons and Menaces the Traveler at Every Step -- A Thrilling Story Fresh From the Frozen Northwest.

(Special from the Chicago Times-Herald)

Frank Phiscator of Baroda, Mich., is back from the Klondike, with his pockets full of nuggets, his purse full of drafts and five times a millionaire, and his experiences in the frozen goldfields form the most thrilling and engrossing story that has yet come down from the Yukon country.

Phiscator became a gold king in 15 months. He went west with money he earned sawing wood. He was backed by two strong arms, a brave heart and a constitution as tough as a knot. He ran a race with death over glaciers, crags and passes, through raging rivers, canyons and rapids, into frozen lakes, killing storms, murderous insects and pests, past starvation, along yawning chasms and under avalanches. It is his verdict that a man who stands the venture earns all he gets. He pities the men who have dared to try the trip. He will be surprised if one-quarter of the crowd that has started gets through alive. He expects to find the trail from Dyea to Dawson strewn with dead when he goes again in March.

This man’s story sounds like the tales from books of adventure where fact has no place. He told it the other night to some men who were preparing to start for the goldfield. They went home converted.

Built For the Journey.

Phiscator looks like the sort of a man built for this journey. He is short, stocky, and weighs 280 pounds. He has a sharp, clear, eye -- an eye of a man that would shoot rather than be shot. His upper lip curls up in an expression of recklessness. His hair is jet black. His neck is short. He walks with a swagger, shakes hand with a hard tug, takes his bracers straight, wears the big, white hat of the west. When he talks, he looks squarely at one, and his talk has the ring of rough honesty.

Here is the way he tells his story:

“It was the Klondike or die a year ago in February. The chances were ten to one I would never come home, and in view of the cheerful outlook I came to Baroda and Chicago to say goodby to my friends and relatives. It seemed a big risk, but I had come to the conclusion to risk all I had as well as my life in one last try for a gold mine. You see, I had had years of roughing it and knew exactly what I wanted to take along. There didn’t seem to be any other man who wanted to go with me, so one cold day I stood alone on the Seattle wharf, about the only white man bound to Juneau.

“It is easy to Juneau. The business of the journey begins right at this point, or it did at least with me. I picked up a fellow on the boat who was pretty brave, and we joined forces. There was but little accurate and detailed information about the country, but what little there was I had. It was all a blind chance, so far as I was concerned, barring the fact that some of the books said there was gold in Alaska for the mere finding. It did not take long for me to conclude that the books were all wrong. It looked for about six months that it would be great luck if we got out with only so much as our lives.

“The trip from Juneau to Dyea was made in a small boat. The weather was bad. The waves ran over the little thing, filling it with water almost as fast as all hands could bail it out. This was a mighty hard hundred miles, but it was a patch of roses in comparison with what came a few days later.

The Start for the Goldfields.

“Dyea was nothing but a dock and a few Indian huts. Charles Fifer, a wanderer from Wisconsin, was in the settlement, and when I told him what I was going to do he concluded to take a hand in the game. My baggage contained enough food for two years, tools which would be needed in case we wanted a boat, and a miner’s outfit. There was but little traffic over the mountains at that time, and the Indians were secured at a reasonable rate to do the packing. We started.

“It went alright for the first two days, the only danger being in crossing ravines and crevices filled with snow. The third day, it snowed -- snowed as it snows no other place but in Alaska. No one can tell or imagine its terribleness. It is not possible to see your hand at arm’s length. There is nothing to do but to get on the lee side of a drift, roll up in blankets and rest on the sleds until the tempest passes. A tent is whipped into shreds in a minute or sent tearing into the canyons. A fire was out of the question, and we ate canned meats that were frozen solid.

“The sides of the mountains and glaciers are so steep that in many places all a stout man can handle is 100 pounds. Their days in which five miles is a good record. The way they do is to take part of the supplies about five miles ahead and leave them on the side of the trail while they go back for the rest. There is not a minute from Dyea to Lake Lindeman when a man is not more likely to die or be killed than he is to get along.

Death on Either Hand.

“We were caught in another snowstorm in the middle of Crater lake. The ice was beginning to break up. It was full of air holes. There was constant danger that we would plunge into one of these if we went ahead, and as great danger that we would be snowed under if we camped. It was almost a face to face proposition with death, and no one, not even an Indian, slept during that night. The next morning the ice began breaking up, and we were constantly dodging big cracks and heaving our sled over heaps.

“Slowly we worked along, not able to use the compass and trusting only to the general information we had from the Indians that we were on the road to reach the Yukon. They did not know anything about the gold mines, and all they did know was that in 30 or 40 days, we might possibly get to our destination. It was no glittering prospect, I can tell you, and just as we were pretty well tuckered out and beginning to wonder if it was worth while we came across the bodies of two men who had died by the wayside.

“We met some prospectors as we got near Lake Bennett. They were out of food and were living off the meat they had made of their dogs. We did not have any more than we would need, but what can you do when men come to you with a plea that they are starving? Flour in that country was worth $60 for 50 pounds, but it had no price with me when I saw the poor wretches who were thinned down to skeletons. They were going back. I never heard whether they got out or not.

Builds a Ship for the Trip.

“Lake Bennett was where we built our boat. The Indians brought down the logs, while I sawed them into boards and then built our ship. A man named Van Wagner joined us here and went through the game. He was a lawyer in Seattle, but he was made of the right stuff. Our ship was about 30 feet long and 6 feet wide, and it was put together to stay. It wasn’t very pretty to look at, but I guess it would have held its own against anything this side of a glacier.

“It was beginning to break up in the spring, and it was much easier sailing than it had been sledding. This lake is about 30 miles long. We got over it in three days without accident. It was, however, only the calm before the storm, since when we drifted into Lake Tagus all the furies on earth and under it were let loose. It blew so hard I really thought the earth would be blown to pieces. The snow fell almost a foot at a time, coming down in great sheets and emptying itself into the boat. We only went three miles in two days and were glad of that. The snow covered up the holes in the ice, and time and again we sank into the ice water up to our necks. It was part sledding and part sailing, and every minute liable to be the last.

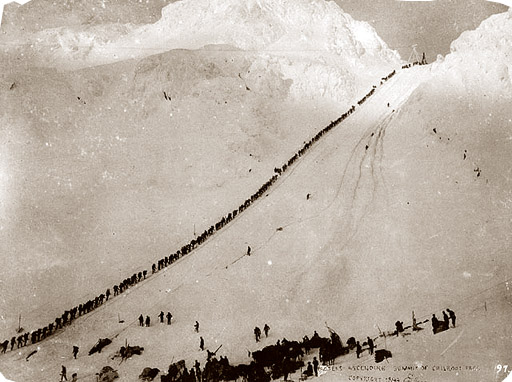

Miners heading up the Chilkoot Pass circa 1898. Some 1,500 steps were carved into the ice.

“The Tagus Indians have a post at the bottom of this lake, and we stopped a day with them, eating large quantities of frozen caribou, which was sickening in its filth, but nourishing after one got it down. It seemed as if we were eating twice as much as we did at home. I tell you I pity the men who have started to the Klondike this year when I read the supplies they have taken. They will run short before they get half way. There is no hope for them. It is likely those who go next spring will find rows of white boards on both sides of the trail. They are gone.

Frightful Dangers.

“If there was danger up to this point, then Lewis river is fire and brimstone. It was like making a trip over Niagara Falls. In the places where it is smooth, the current is at least seven miles an hour, and in the places where it is rough it runs 40 miles an hour if an inch. It is filled with big rocks, some of which stick up in sight, others of which stay just below the surface.

“A scow ahead of us had seven men in it. All hands were at work with the oars, trying to keep it headed clear. We were coming along faster than steam launches. There was a cry from the company in front. In a minute the boat was cut squarely in two. A rock had torn through it like an ax. The men floundered around in the ice water. Part of them got out. The others went down. All the provisions were lost.

“This was more encouragement. We ran into the shore and did all we could for the poor wretches, and the last we saw them they were sitting disconsolately on the bank, wondering whether to try to get out or to press on. I have never heard of them since.

“There is no man who can figure how many men are lost each year in trying to make this trip. Bodies are found all along the way. They are tangled in the driftwood of the eddies or thrown up on the ice. The miners usually dig a little grave for them. Many of them do not have any papers on them, and I suppose they go down in the list of the missing. I predict there will be plenty of missing next spring when navigation opens up and the people begin to come out.

Cold Water That Kills.

“It seems almost impossible for a man to do anything in the water up there. It is so cold that it seems to kill in a very few minutes after they get into it. It makes no difference how expert swimmer the man may be. I never saw one in any of the rivers who could get out alive.

It took us 56 days to get to the Yukon, and we danced a set with death every day. The river was about a quarter of a mile wide where we entered it and flows in such a torrent that we had to keep near the shore. It is lined with rocks and trees that threaten to swamp you, but with the greatest caution we finally pulled up at Forty Mile Post on Forty Mile creek.

“There was great excitement at Forty Mile when we returned. A prospector had come in from the Klondike district with the information that he had struck it rich. There was a wild scramble to Bonanza creek, the location of his discovery. I started the same night, poling 55 miles up the Yukon before noon the next day. An hour in time on that trip might have meant a million in money, and it is wonderful how a man will work when an hour’s extra labor may settle things for him for the balance of his life.

“We did not want to be handicapped in the race with our provisions, so we left them on the shore of the Klondike with some Indians. This left us free handed, and we scudded over the mountains, carrying only our mining outfit, about 100 pounds to the man. We were among the very first to reach Bonanza, staking four claims in the richest part. They did not seem to pay as much as we expected, and so we concluded to go back and try some place else, holding our claims in case of emergency.

The First Find.

“We were creeping down from Bonanza when we came to a camping place a little below the mouth of El Dorado. I think the men with me were ready to throw up their hands. They were glad to act as cooks on an offer that if they would cut the wood and get the meals I would take a run up to El Dorado and see what I could find. It was about all I could do to get my 100 pounds on my shoulder and get started. It was apparently the last chance, as the grub was out, and there was none to buy and no money to buy with.

Panned Out a Quarter.

“I confess I was feeling a good deal like a man just waking up from a good dream. It was a hard mile and a rough mile to the creek, and with a discouraged heart the tools were unpacked and the old pick again whacked into the ground. You can’t tell there is gold in the ground by the way it looks, and I don’t think I expected to find a bit of the yellow metal within 40 miles of where I was working. There was a little

excitement and watching the first pan, and I tell you I handled that shovel full of Alaska gravel with great care. The sand gradually ran out, and with close searching I was able to get together about 25 cents’ worth of yellow dust. It was a big come down from the stake set when we left Montana, but it was the only stake in sight at the time. It was that or nothing.

“It was a joyful night in Phiscator camp that night, if it was not very hot. The boys were happy even in their hunger, and could hardly wait for morning to get into the field and locate. My claim was No. 1, and the others took claims on both sides.

“We actually danced up the El Dorado about 8 o’clock next morning. I think each of us could have carried a ton. We forgot hunger and weakness, with only very poor wages in sight. It was our only hope, and we made the most of it.

“I went to work on the spot where I had earned the 25 cents the next day. It was good I was of a stout and rugged disposition. I shoveled one scoop into the pan and began to sift. I got a nugget worth $7. It was enough to cause heart disease. The other men did as well, and there was no doubt we had made our pile.

“We three were the only ones on the creek. We saw there was no danger that our claims were not clearly marked, and then prospected all the way up the stream, about 30 miles. We found it good in spots and bad in others -- finding at least 30 locations where one was as good as the other.

Riches Going to Waste.

“We sat in our tent at night and almost wept that we could not get word back to our friends. We saw millions, with no one to claim them. I do not think a claim of the 30 is worth today a cent less than $1,000,000 each. The law allowed us only three -- one each.

“This much for the way we found it and the time we had in finding it. This is the way the gold runs after you have a good claim.

“It is possible to work the claims about 2½ months a year. You can’t get water any of the balance of the time. I put in this amount of time on my claim and took out exactly $96,072. It was done by myself and two men, who earned $15 a day as laborers.

“It is beyond comprehension to imagine the richness of the soil. During the summer we worked over a space 86 feet long by 35 feet wide to the depth of 4 feet. The find was $49,084.

“The biggest pan ever turned out on the claim held $52. Berry, who has a claim near by, beat this by picking his dirt. He got $595 at one sifting. The nuggets run from $15 to $40.

“It sounds big and comfortable and pleasant, but I want to tell you that it costs all it is worth.

Horrors of the Climate.

“There are troubles in the air and on the ground and everywhere. It gets down to 73 degrees below zero and sticks there for ten days at a stretch, and it is all bosh about the cold being so dry that it is not felt. It is the coldest cold out of doors. It will run along at 60 degrees below zero for three weeks or a month at a time.

“It is so cold that the ground is frozen to a depth of 30 feet. It does not thaw out in the summer time, even under the redhot sun. The cold from the frost comes up through the moss, and in the middle of August the cold oozing out of the ground freezes the low places.

“The winter days are horrors. The sun gets up at 9:30 in the morning and disappears at 2:30 in the afternoon. It snows all the time, and there is nothing to do but keep from freezing to death.

“In the summer, the sun hardly ever gets out of sight. It is daylight at midnight. The sun gets to a point which looks about 15 feet above the horizon and then starts back. It never sets.

“If one likes this sort of a thing, he can get rich at the Klondike.

“My advice is, all tenderfeet had better stay home and live than try to get rich in the Klondike. It has more kinds of death than any place on Earth.”